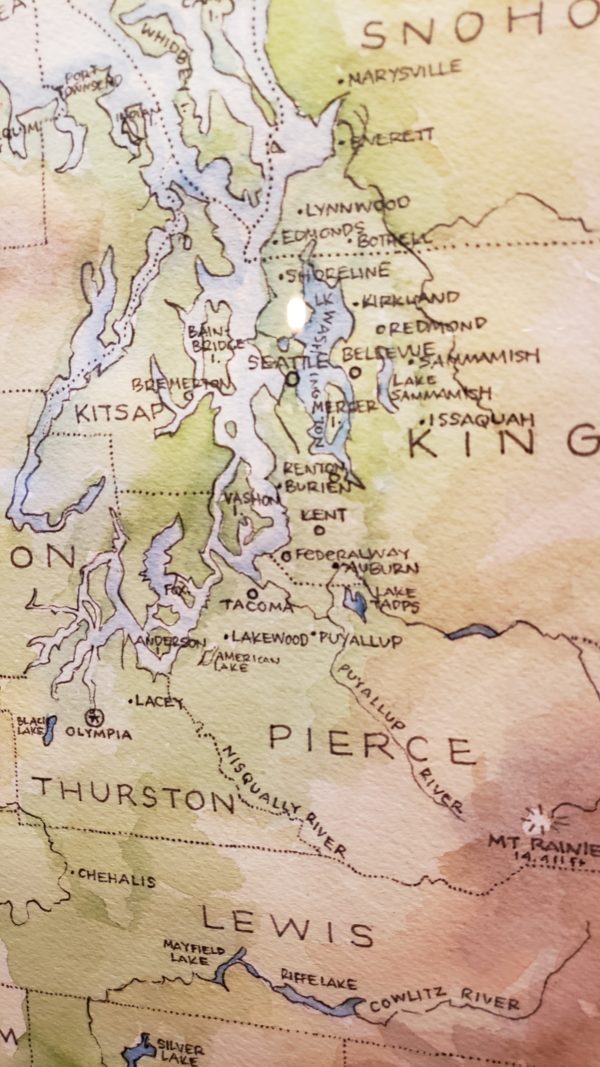

One of the more common issues I’ve seen with maps of cities in fantasy settings is their regularity. Short of a city being developed according to a master plan from the beginning or being rebuilt from scratch after a calamitous disaster, no city is going to be perfectly regular and even something like the Great Fire of London or the KantÅ Earthquake still didn’t result in a uniform and elegant city design. There are many reasons for that, though I think the two chief reasons are human nature and natural features. People rarely relinquish their property, even if shaving off a hundred square feet on one side would allow a street to run in a straight line, and will rebuild on the same land, given a choice. For the same reason, rocky hills are notoriously hard to shift and rivers meander, so construction of houses and streets tend to conform to the landscape rather than vice-versa short of modern feats of engineering and, even then, only where the effort involved has a clear payoff. I live in Seattle and we’re quite familiar with the modern engineering that resulted in the Denny Regrade, whereby Denny Hill was leveled to allow for northerly expansion of the city. Even then, not everyone agreed to the plan and, like urban planners in modern China, the “spite mounds” in Seattle have their parallels with China’s “nail houses”.

Rules regarding cities may be thrown out the window in a fantasy setting and, as I’ve always thought, magic can substitute on some level for a degree of modern engineering. A sufficiently motivated dragon could substatially alter both the landscape and the disposition of human (or non-human) settlement in an area. Even more drastically, Japan’s legend of the yo-kai Namazu the Earthshaker was the cause of earthquakes and, if freed, could wreak much greater destruction and that’s just one of many beings around the world spoken of in myths and legends. Short of that, a more realistic city grounded int he real world is one that develops over time.

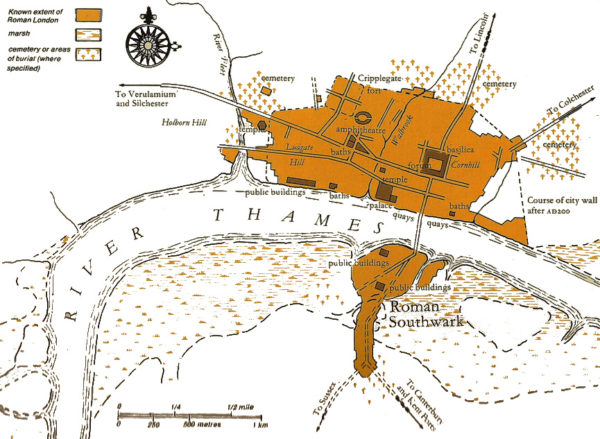

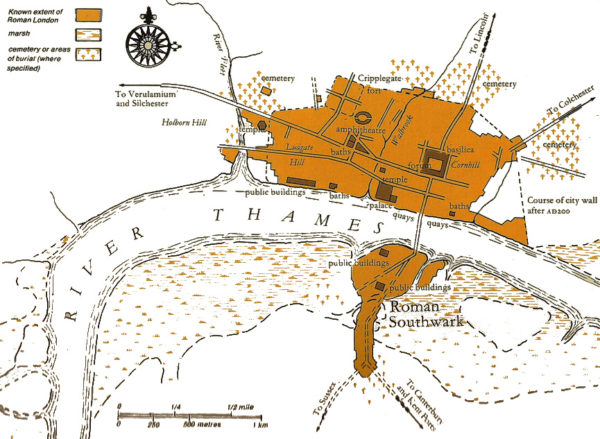

The typical settlement may develop at the bank of a river, atop an easily defended rocky outcropping, beside a sheltered bay, and many other such places that offer arable land, fish or game, or other ready source of food along with protections from storms and flooding or other natural disasters like fires, mudslides and volcanic eruptions. Even then, settlements may arise in inhospitable areas if that’s the only place to live close enough to rare resources like precious metals or gemstones. If the settlement exists along a trade route or main path of travel (for example, as a seaport conveniently located as a stopover point), it may grow. As it does, walls and fortifications develop and other structures are added to facilitate travel, trade, and mercantilism. Increasingly, housing for permanent and transient populations multiply and entertainment venues also develop. In a planned sense, a Roman settlement offers all of these, typically following a fairly uniform plan with a fortified camp, a forum and basilica, an amphitheater, several temples, markets, and bathhouses, all enclosed by a wall. As cities grow, they often incorporate other settlements and expand beyond the bounds of their original walls. Those existing structures may constrain development much the same way natural land features do.

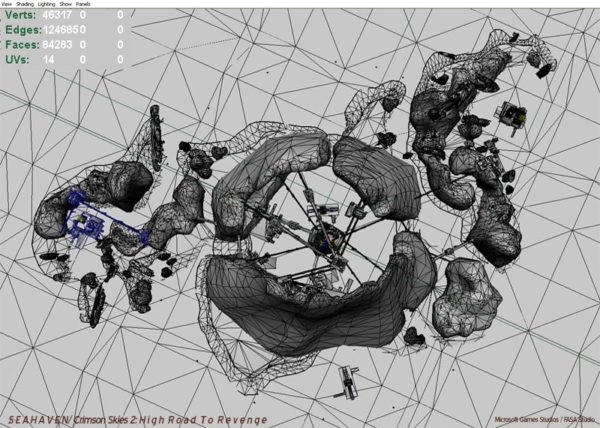

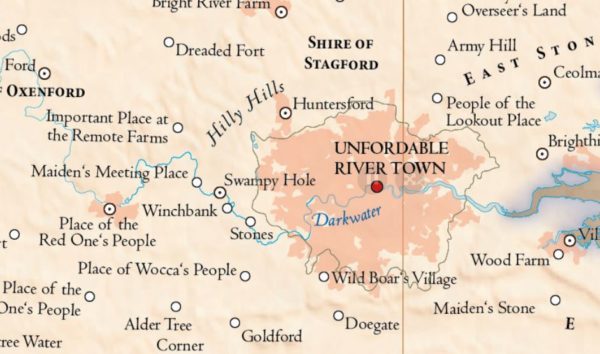

Ankh Morpork river crossing thumbnail by Charles D. F. Board

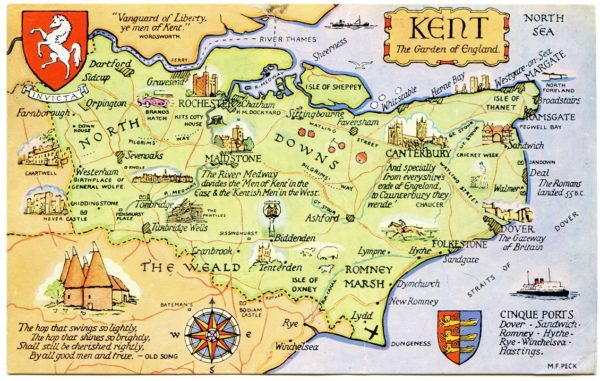

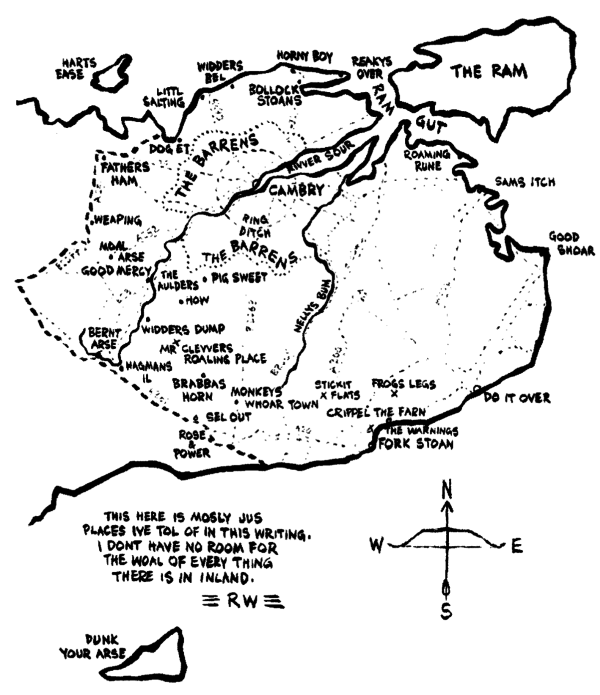

For all of the reasons enumerated, I think it’s great when an experienced urban planner offers up his rendition of the evolution of Terry Pratchett’s Ankh Morpork. Not only does it offer some great insights into how the great circular city might develop, but it allows for comparison to a similar riverine city like London from its beginning as a Roman settlement to its later habitation during Anglo-Saxon times and its later fortification in the Middle Ages.

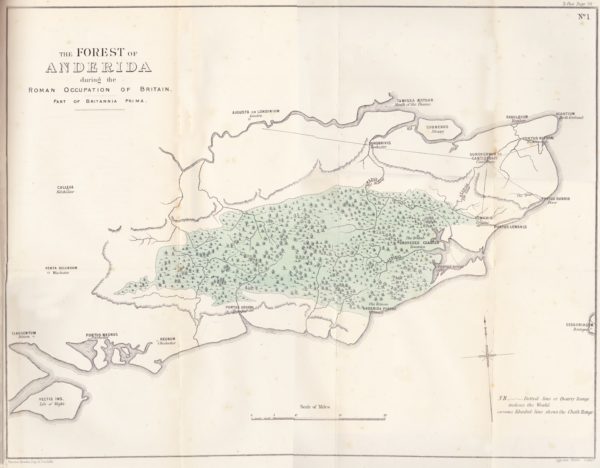

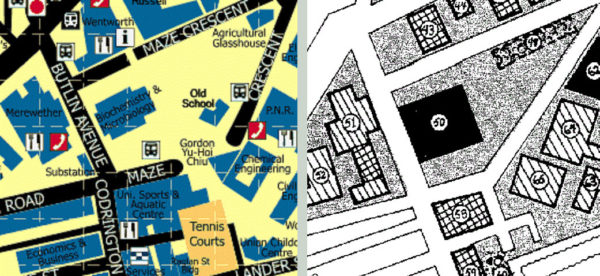

Roman London known extent with major structures